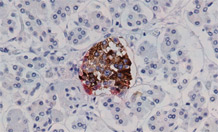

Insulin-producing cells (brown) in people with longstanding Type 1 Diabetes

Insulin ‘still produced’ in most people with Type 1 Diabetes

New technology has enabled scientists to prove that most people with Type 1 Diabetes have active beta cells, the specialised insulin-making cells found in the pancreas.

Type 1 diabetes occurs when the body’s immune system destroys the cells making insulin, the substance that enables glucose in the blood to gain access to the body’s cells.

It was previously thought that all of these cells were lost within a few years of developing the condition. However, new research led by the University of Exeter Medical School, which has been funded by Diabetes UK and published in Diabetologia (the journal of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes), shows that around three quarters of patients with the condition possess a small number of beta cells that are not only producing insulin, but that they are producing it in response to food in the same way as someone without the condition. The study, which was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, through the Exeter Clinical Research Facility, tested 74 volunteers. Researchers measured how much natural insulin they produced and whether it responded to meals, a sign that the cells are healthy and active. They found that 73 per cent produced low levels of insulin, and that this occurred regardless of how long the patient was known to have diabetes. Researchers studied the response of the insulin production to a meal to prove that the low level insulin production was coming from working beta cells.

Dr Richard Oram, of the University of Exeter Medical School, led the study. Dr Oram, who is based at the Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust's Blood Sciences Laboratory, said: “It’s extremely interesting that low levels of insulin are produced in most people with Type 1 Diabetes, even if they’ve had it for 50 years. The fact that insulin levels go up after a meal indicates these remaining beta cells can respond to a meal in the normal way - it seems they are either immune to attack, or they are regenerating. The researchers used new technologies which are able to detect far lower levels of insulin than was previously possible. The levels are so low that scientists had previously thought no insulin was produced.”

Dr Matthew Hobbs, Head of Research for Diabetes UK, said: “We know that preserving or restoring even relatively small levels of insulin secretion in Type 1 diabetes can prevent hypoglycaemia (low glucose levels) and reduce complications and therefore much research has focused on ways to make new cells that can be transplanted into the body. This research shows that some of a person’s own beta cells remain and therefore it may be possible to regenerate these cells in the future. It is also possible that understanding why some people keep insulin production whilst others lose it may help answer key questions about the biology of Type 1 diabetes and help advance us towards a cure for the disease.”

Type 1 diabetes affects around 200,000 people in the UK alone. The disease commonly starts in childhood and causes the body’s own immune system to attack and destroy the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas, leaving the patient dependent on life-long insulin injections.

Dr Oram said: “We are now able to study this area in much more detail. By studying differences between those who still make insulin and those who do not, we may help work out how to preserve or replenish beta cells in type 1 diabetes. It could be a key step on the road to therapies which protect beta cells or encourage them to regenerate.

“The next step is a much larger-scale study, to look at the genetics and immune systems of people still making insulin, and to answer the important question of whether the complications of Type 1 Diabetes are reduced in people with low levels of insulin.”

One of the participants, Alex Nesbitt, from Devon, was diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes 36 years ago, and is monitored by an insulin pump which is permanently attached to his body. He said the condition was “trying in the extreme”, particularly because of the stigma attached to the condition. He said: “For a very long time, people have believed that if you have Type 1 Diabetes, that’s the end of your insulin production. This study raises some major questions about whether that’s actually the case. It’s very exciting for current opinion to be challenged in this way, and I’m fascinated to know what difference it will mean for the future.”

Cells mage from a JDRF Network of Pancreatic Organ Donors medallist, courtesy of Pia Leete.

Diabetes monitoring image via Shutterstock.

Date: 10 October 2013