Articles

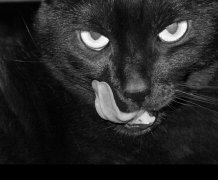

The black cat was a relatively late development in the history of witchcraft, new research has found. Credit: FreeImages.com/Mateusz Piatkowski

The first witch’s cat was white and spotty – and called Satan

The black cat, now a crucial accessory for Halloween witches, was a relatively late development in the history of witchcraft, as the stereotype of the witch evolved alongside perceptions of women, research by Professor Marion Gibson, Professor of Magical Literatures at the University of Exeter, has found.

The earliest witches were not depicted as old or repulsive: they could be young, pretty and noble, with white or tabby cats, dogs, lambs, toads and ferrets as magical companions.

Research by Professor Marion Gibson, Professor of Renaissance and Magical Literatures at the University of Exeter and the author of several books on witchcraft, has found that the way witches were perceived has reflected the status of women through the ages.

Exeter was the site of the last hanging for witchcraft. Three elderly women were hanged in 1682.

Witches were seen to need the devil’s help, because they had little power in their own right as women. Some were thought to ask the devil for money, goods and the power to make neighbours and lovers do what they wanted.

Witches’ companions were believed to be the devil, disguised in the form of a small animal, sent to help them do magic on the sly.

Black cats only became part of the witch stereotype in Victorian times. The first witch’s cat to hit the headlines (in a 16th century newspaper) was a white spotted cat, called Satan. Satan belonged to Elizabeth Francis, from Essex, who was accused of using the cat to punish a lover who refused to marry her.

Francis is also accused of sending the cat to neighbours she didn't like, causing them to fall ill or die. Elizabeth was accused of witchcraft in 1566 but was spared hanging.

In 1582, Ursula Kemp, a healer and “good witch” who helped her neighbours in childbirth and with their rheumatism, did not escape the noose. Kemp had two cats, one black, one grey, called Tiffin and Jack.

She was relatively young and had an 8 year old son but, after being convicted of witchcraft, was hanged. Kemp also had a white lamb and a black toad according to her son, whose evidence helped to convict her.

Another witch, Joan Prentice, had a ferret called Bid. He is said to have arrived out of the blue, announcing “I am Satan. Fear me not”. Elizabeth Stile had a rat named Phillip. Alice Gooderidge had a ginger and white dog named Minny.

Research by Professor Marion Gibson, Professor of Renaissance and Magical Literatures at the University of Exeter and the author of several books on witchcraft, has found that the way witches were perceived has reflected the status of women through the ages.

Witches were seen to need the devil’s help, because they had little power in their own right as women. Some were thought to ask the devil for money, goods and the power to make neighbours and lovers do what they wanted.

The caricature of a witch as an ugly, stooped hag living in squalor took hold in the 16th century as witch trials became more common, perhaps because an economic downturn made older women, especially poverty stricken widows, more vulnerable. Before then witches were more often recorded as young, charismatic and noble. Broomsticks, appear in medieval illustrations but along with pointy hats do not become a must-have accessory for witches until around 1720.

In 1441 Eleanor Cobham, Duchess of Gloucester, was accused of witchcraft, including necromancy and raising the dead. It was said she had paid astrologers to foresee the king’s illness or death. Her fellow-witch Margery Jourdemayne was burned at the stake. Eleanor, who was wealthy and famous, was only made to do penance, parading through the streets in a white robe. Professor Gibson believes she may have inspired the fictional scheming noblewoman Cersei Lannister, in Game of Thrones.

Around the 16th century the stereotype of a witch - a repulsive, hobbling old woman – became popular. In 1584 Reginald Scot, a Kentish gentleman-farmer, wrote that a witch was likely to be: a woman who was “old, lame, blear-eyed, pale… and full of wrinkles; poor, sullen, superstitious”.

By Victorian times - and often with American influence - artists had added pumpkins and broomsticks. The witch was becoming the Halloween caricature, represented by the Wicked Witches of the East and West in the 1939 film, the Wizard of Oz, and witch/queen in the 1937 film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

During the First World War, however, radical women fighting for suffrage and women working in the war effort rediscovered witches and the witch was rehabilitated in the popular imagination. Novels at the time even depicted powerful young female witches from Britain and Germany holding magical battles with wands over London, Harry Potter style.

Stella Benson’s 1919 novel Living Alone featured a witch who made people's lives better – happier, more imaginative, freer. She lived alone too: that was a new thing for women. The heroine of the story, a bold and powerful witch fought a magical battle with a German witch in the air over London.

In 1926 Sylvia Townsend Warner wrote a novel, Lolly Willowes in which a woman becomes a witch as a way to escape from her controlling male relatives. She curses one of them to be stung by wasps, and makes a pact with the devil.

The witch in fiction evolved alongside perceptions of women. In the 1960s and early 1970s the witch in Bewitched was a charming housewife. The witches in Harry Potter had various roles and could be powerful and scary in their own right. So the old witch stereotype with black cat, pointy hat and broomstick is not the whole story of witches.

Between 50,000 and 200,000 people are estimated to have been executed as witches across Europe, mostly in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The last Witchcraft Act was not repealed in England until 1951: it was used to prosecute spiritualist mediums and fortune-tellers.

Covens of ‘real’ witches are still found around Britain and around the world. Earlier this year, women calling themselves witches – including a ‘coven’ in New York city - put a spell on Donald Trump.

Date: 31 October 2017