articles

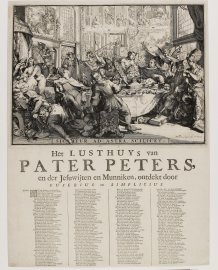

Romeyn de Hooghe, Sic Itur ad Astra Scilicet, 1688, etching and letterpress, British Museum, London. ©The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

The Glorious Revolution inspired birth of modern satire long before coffee shop culture, according to new research

The arrival of William of Orange in England helped to inspire the birth of modern satire – long before coffee shop culture made the cutting art form fashionable, a new study argues.

The golden age of satire in Britain was in the 1740s, but it arrived in the country – via the Netherlands - half a century earlier, when the Dutch prince needed propaganda to cement his position in Britain and Holland, according to the research.

William III needed the protection, and money, of powerful men in Holland. He supported Dutch printmaker Romeyn de Hooghe, whose portrayal of him contributed to the success of the Glorious Revolution.

In funny and crude prints, produced between late 1688 and the summer of 1690, William III is portrayed as a sober and valiant defender of Protestantism against the Catholic kings, James II and Louis XIV, who appear as a darkly comic duo, misguided followers of a primitive religion committed only to their own egos.

These satires were designed to encourage doubt about the motives of James II, Louis XIV, and, on the domestic front, the Amsterdam regents. They helped to maintain support for William in the Dutch Republic, without whose financial backing William III’s invasion of England and consolidation of power would not have been possible.

Dr Meredith Hale, from the University of Exeter, has carried out the first detailed analysis of the satires, including translation of the texts into English, to show how De Hooghe responded almost immediately to the rapid unfolding of events in Holland and England, dating some of the satires to within weeks of the events they depict. She argues that they are the first printed political images which can be classed as modern political satire.

Dr Hale said: “Political satire has long been considered to be an eighteenth-century British phenomenon, generated by London’s news-driven coffee-house culture. I believe political satire, as we know it, in fact, emerged earlier, in the late seventeenth-century Netherlands in the contentious political milieu surrounding William III’s invasion of England.

“Romeyn de Hooghe’s satires were at the heart of the most important development in the history of printed political imagery. The prints established many of the qualities that define the genre to this day, the crude treatment of the body, text and images used together and serialised production.”

In the Netherlands, unlike England, there was an open market for print making and few restrictions on the imagery which could be used. The satires were designed to appeal to Dutch audiences, but a small number of impressions were brought to England by ambassadors and traders, and may have circulated among printmakers and print dealers.

One image, released to coincide with William’s landing at Brixham on 15 November 1688, was designed to warn people of the threat posed by an Anglo-French conspiracy to return England to the Catholic Church.

In the satires on domestic politics the powerful of Amsterdam are accused of colluding with France in order to maintain lucrative trade alliances and marginalize William III politically. In Mardi Gras de Cocq à l’Ane, the Amsterdam regents appear as carnival stooges offering their city to a fully armoured Louis XIV, who sits on a toilet, preparing to wipe his bottom with their rights and privileges. In Nieuw Liedt (New song) the Amsterdam regents appear as ‘figures sprung from shop signs’.

The satires would not have circulated widely. They would have been collected by the political elite who most likely kept them in albums of prints. The delicacy of the etching technique (relative to engraving) and the complexity of De Hooghe’s compositions meant that only around 1,000 impressions of each plate could have been produced. The prints are now held in museums around the world, including the British Museum, the Rijksmuseum and the Royal Library in the Hague.

There is no proof that William saw the prints, but he almost certainly knew of them. His right-hand-man Hans Willem Bentinckwas in direct contact with De Hooghe, and when the printmaker was in trouble with the authorities in Amsterdam, William stepped in to protect him, ensuring that only De Hooghe’s collaborator, who wrote some of the satirical texts, was jailed. De Hooghe was commissioned to produce other images of William throughout his life including his and Mary’s coronation and the Dutch Armada setting off for England.

Romeyn de Hooghe, who lived from 1645 until 1708, produced a huge body of work which also included maps and book illustrations. In 1690, in response to his domestic satires, De Hooghe was accused of blasphemy, atheism, and sexual perversion by the powerful in Amsterdam, allegations that marred his reputation from the time of his death through the middle of the twentieth century.

The Birth of Modern Political Satire: Romeyn de Hooghe and the Glorious Revolution is published by OUP Oxford.

Date: 22 January 2021